Chapter 8

The greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic

Peter Drucker

Have you ever wanted something so bad, you overlooked your gut feeling? We have a built-in early warning system that gives important signals through feelings and body sensations. It indicates if you’re getting warmer—aligning with your goals and dreams—or cooler and farther away.

Once we get attached to an outcome, we tend to ignore red flags and plough ahead. Instead of pausing, listening, and questioning the disconnect, we’re driven to achieve a goal. We get fixated on our viewpoint instead of fascinated by the possibility of what might be.

No matter how much personal development training or self discipline we have, it happens. Such is the pitfall of being human. It recently happened to me.

A not-for-profit organization in my community that serves business start-ups was looking for new board directors. When I first moved here, people told me the organization was exclusive, not well connected to the broader community. That struck me as odd since it was publicly funded. I suspected the board was operating without effective processes in place.

I had board development experience and had served on a public board with a $70 million operating budget. I thought I could help the not-for-profit build a solid foundation for growth and community engagement. I knew how internal board practices, done right, can strengthen external community connections for an organization.

Boards usually publish the skills mix they want directors to have. I asked to see the skills matrix to see what skills and expertise were being recruited.

I never heard back from the chairperson, nor did I receive a skills matrix. But I did receive a call from a director. We had a candid conversation about the organization’s history, challenges, and plans. The board prioritized strengthening community connections, developing policy, and implementing responsible governance. It appeared to us both that I was a good fit.

Based on our conversation, I agreed to seek nomination as a director. The director told me that I’d just been screened and our conversation had been my interview. Wait. What? I’d skipped the application process and gone straight into the interview pool.

The first red flag went up. I ignored it. I wanted to join the board.

There wasn’t sufficient time between the “interview” and the annual general meeting to go through the formal nomination process. A decision was made to appoint me for a one-year term at a regular board meeting held immediately following the AGM. It was a workaround, a loophole that made it possible for me to be elected. I felt uncomfortable going about my nomination this way. My intuition was speaking to me again, but I wasn’t listening. I joined the board.

The organization had committed to the major sponsorship of a large, high-profile event. Several new directors had questions about the investment, benefits, public access, and perceptions of exclusivity. They wanted more information in light of allegations that local entrepreneurs had been excluded in previous years. Other directors minimized these concerns and pushed for the vote. Although I had no objection to the event, the way the vote was rushed through left me with a knot in my stomach. The second red flag went up.

Staff were capable, passionate, and enthusiastic. Clients raved about programming. Directors were honest, hard-working professionals. There was no question about the team’s commitment, dedication, and intelligence. All the fundamental components for full community engagement were in place. The only thing missing was a board culture that welcomed healthy conflict.

A task-oriented chair, although well intentioned, can be one of the worst offenders for shutting down the magic that is available through group dialogue and collaboration. Don’t get me wrong—brevity is important in respect of people’s time. But if time restrictions suppress questions and prevent the sharing of information, the real decision making will take place outside the boardroom, in informal networks. Nobody will get anywhere near the groan zone—or the Possibility Zone.

By shutting down healthy conflict and open dialogue, important reservations that may not be obvious at first do not surface. When conversation remains superficial, the organization misses out on the hidden assets that emerge through deep commitment and meaningful buy-in.

In the case of this board, there was a disconnect between the stated intention of group deliberation and the actual practice. Probing questions weren’t welcomed. Although there was nothing serious or malicious going on, it didn’t feel right to bump up against an invisible wall at the boardroom table.

Trust was missing, but not because people at the board table weren’t trustworthy. The organization, like so many, ran by meeting agenda. There was no overarching structure to build relatedness, open dialogue, or foster trust. In the absence of process, the environment felt cliquey and political. I realized the “participatory decision-making model” was dead in the water when the board declined my offer to present a fifteen-minute segment on board development. The third red flag went up.

People want to contribute, not be rubber stamps. On this board, contributions from certain members carried more weight, and everyone knew it. Regular directors struggled to make it past the gatekeeper.

I should have listened to my intuition when the first red flag went up.

I should not have accepted a seat at the boardroom table knowing that proper protocols hadn’t been followed to get me there. In the words of R. Buckminster Fuller, “Integrity is the essence of everything successful.” I did not seek re-election at the end of my one-year term.

In his book Overcoming the Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick Lencioni presents a conflict continuum. On one extreme is artificial harmony, as I experienced on this board. The other extreme is destructive conflict, the kind of environment that provokes mean-spirited attacks. The ideal conflict point is in the middle.

When the stakes are low and implementation is easy, quick decisions are great. But if the driving force behind the decision is to come up with an innovative solution or an agreement that will be upheld and defended over the long term, there’s only one way to get there—by reaching an integrated, inclusive decision or action plan.

Inclusive solutions are usually not obvious at first glance. That’s what makes original thinking so elusive and rare. Deep feelings of accomplishment and satisfaction for a job well done accompany these types of breakthrough agreements. Trust increases, priming the pump for the next round of decision-making.

When emotion goes up, intelligence goes down

Blair Singer

So what, exactly, should we do to keep the conflict point balanced, so our Possibility Zone doesn’t devolve into a groan zone? I have three suggestions:

The Wise Observer

An old tale from the Indian subcontinent tells of six blind men who came across an elephant, a creature they had never encountered before.

“It’s like a pillar,” said the first man, touching its leg.

“Oh, no! It’s like a rope,” said the second man, touching its tail.

“What?” said the third man, touching its trunk. “It’s like a tree branch.”

“How can you say that? It’s like a fan,” said the fourth man, touching its ear.

“It’s like a huge wall,” said the fifth man, touching its body.

“You are mistaken. It’s hard, like a pipe,” said the sixth man, touching its tusk.

They began to argue. Each man, aware only of his own perspective, insisted he was right. A wise observer was passing by and heard the argument. The observer paused and explained, “Everyone is right. You are describing it differently because each of you understands only one part.”

How often do we argue like the men in the parable, sure of our own perspective but blind to the larger picture and to our own biases and emotional triggers? No matter how opposed the parties are, a common denominator exists. Participants need to be able to put themselves in one another’s shoes, take time to understand differing perspectives, and question without judgement. Sticking with the process can reveal major epiphanies. It’s common for people to discover their opinions are misinformed or their thinking is out of date.

However, the process requires at least one wise observer.

If trust is low or problems have been festering for a while, it may take an impartial listener to defuse emotion, identify patterns, and remove structural impediments so new processes can emerge. An experienced facilitator, someone holding the space for systems leadership, can help groups to see the elephant in its entirety.

Stop, Drop, and Roll

“When emotion goes up, intelligence goes down.” When I say that to myself, the words stop me in my tracks. My mood lightens, and I can shift gears internally.

People think and react at lightning speed. It’s hard to drive a wedge into a conversation that’s heating up. But it can be done. What you need is a process, a structure to interrupt your usual pattern.

As a child, did you learn the three-step fire safety technique stop, drop, and roll to prevent injury if your clothes caught on fire? Just like a fire, a heated conversation can be extinguished by depriving it of oxygen—judgement and blame.

When a discussion heats up and emotions start to burn, use the stop, drop, and roll technique to put the fire out.

1. Stop. Recognize the communication isn’t working. Shouting, swearing, and digging in heels will only fan the flames and hamper attempts to resolve the issue. Identify where each party sits on the innovation curve. Who is initiating this conversation?

2. Drop. Drop the personal focus. The issue is systemic, not personal. Don’t make the conversation about personalities. Instead of saying, “Joe’s not pulling his weight,” say, “We’re not meeting our production targets in the button department.” As soon as you make the issue about Joe, you trigger resistance and defensiveness. Dropping the personal focus instantly improves the dynamic.

3. Roll. From how a seed grows to how a star is formed, a system underlies everything in the universe. Systems are circular—a series of processes that need to happen before an outcome is achieved. Remember: roll equals round, and round equals systems. When you focus on the system, no one is being blamed. Everyone can analyze the problem together. From this perspective, viable new solutions can be seen.

The effectiveness of stop, drop, and roll lies in its ability to interrupt automatic, reactionary patterns.

When you feel tensions rise, check your own energy first. What are you transmitting to the team? Is it positive, negative, or neutral? Your energy affects others.

Awareness is important because strong leaders recognize and nurture others. When the people around you start to behave strangely, they are likely taking directions from their backseat drivers. When people doubt themselves, are fearful, or have personal or financial situations making them feel desperate, the emotional tension comes out in their words, behaviours, and body language.

Helping others to see what’s going on, moving the conversation to systems, and listening without judgement are powerful motivators of change. It’s not your job to fix their issues; you’re not a counsellor. Your role as leader is to be a rock, a stand for possibility.

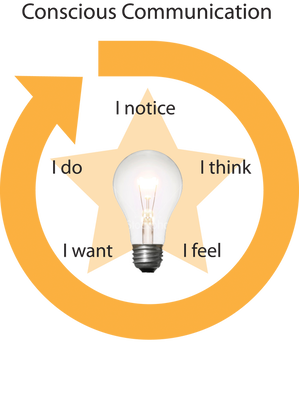

Conscious Communication

When you feel emotional tension rise, that’s both your cue to act and your choice point. Seize the opportunity. A situation needs resolution. If you step over tension, pretending it isn’t there, you add to the discomfort and prolong the agony. Open communication is the only way to clear the air.

I practice Conscious Communication in combination with stop, drop, and roll. Conscious Communication is my five-step formula to diffuse difficult situations with the skill of a bomb expert.

Conscious Communication uses a carefully sequenced structure to maximize results and reduce the likelihood of triggering defensiveness in others. The step-by-step format defuses built-up tension like a bomb squad defuses an explosive device. Conscious Communication is about learning to separate the facts (outside observations) from the meaning (internal interpretations) we make up about what we perceive.

Step 1. Start by saying, “I sense …” or “I notice …” You are looking for external observations that you can see, hear, or touch. Focus on concrete facts, a pattern, results, or the absence of results. For example, “I notice the information package I am to review as a board member arrives they day before our meetings.”

Step 1 focuses the conversation on evidence of what’s going on, such as missed deadlines, repeated patterns of absenteeism or tardiness, lack of consultation, or quality deficiencies. In Step 1 you are simply making the current reality explicit.

Step 2. Continue with “I think …” or “I believe …” to share your opinion or interpretation of what you observed. For example, “I believe it is important for board members to show up at meetings fully prepared to participate in deliberations in a responsible and informed way.”

In Step 2 you are getting present to the original intention, initial commitment, or promises made to key influencers (customers, employees, suppliers, and lenders). Addressing the standard of performance that is necessary and expected clarifies the optimal outcome, or ideal future, and shows that a gap exists.

Step 3. Thoughts happen at lightning speed, making them hard to differentiate from our emotional response. “I feel …” captures your emotional response. Our thinking drives our feelings, which in turn drive our thinking—unless we insert a wedge. Ask yourself, “What thoughts are fuelling this feeling?” Communicate them in an “I feel …” statement. For example, “I feel it’s essential to good decision-making that volunteer directors have adequate time to review board materials in light of all the other responsibilities they have in their own businesses.”

In Step 3 you are sharing the sense of urgency you feel toward closing the gap, or the impact you envision if no action is taken. This step addresses the ramifications of ignoring the current reality, or exposes the unintended consequences of allowing the gap between the current reality and ideal future to continue.

Step 4. What do you want the outcome of the conversation to be? What result are you looking for? Sorting this out in the moment is challenging, so think about the outcome before starting the conversation. Express it using an “I want …” statement. For example, “I want to see a lead time put in place to ensure directors receive the board package five to seven days in advance.”

Keep a solution-oriented focus when presenting Step 4. What do you want to see, hear, or experience when the gap between the current reality and ideal future has been closed? What will it be like for people when the gap is resolved?

Notice that you are four steps into the process, and four impactful sentences have been communicated. Still, no one has been blamed or accused. You are sitting on the same side of the table with the people who are accountable, inviting them to observe and analyze the system. In presenting your case for action in this way, you are inviting partnership in solving this problem instead of triggering defensiveness or resistance. You are creating a safe space for reflection and critical thought.

Step 5. “I do …” Think about the role you are willing to play to resolve the issue. Can you commit to assist? If you are giving feedback, be specific. For example, “I am happy to share best practices from other boards I’ve served on to help us map out a process and preparation timeline.”

Like the blind men touching the elephant, consider that the people in the room with you may never have looked at the issue from a systems perspective. You’re giving the accountable parties the benefit of the doubt. This powerful conversation is like hitting restart on your computer. What resources, support structures, and opportunities for action are now available?

Effective communication enables people with diverse perspectives, needs, and interests to focus on a common goal: improving the system so it works for everyone. Transparent processes encourage accountability and prevent politics from undermining participation.

Remember: Heading straight for the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow won’t work. Learn to turn diverse interests into creative collaborative energy and harness it in your systems to generate the flow of clients and money summary text.

© Discovery Centre for Entrepreneurship Inc. 2006 – 2024. All rights reserved.

We use essential cookies to make our site work and to improve user experience and analyze website traffic. By clicking “Accept,” and/or continuing to use our website you agree to our website’s cookie use as described in our Privacy Policy.